As MLS heads into 2026, a common refrain I've heard from Sounders fans is that the club seems to have an affinity for players who have recovered from knee injuries. While the refrain is pretty funny, it got me thinking. With the World Cup coming to North America and even the NFL Players Association crusading for grass fields, what impact, if any, do playing surfaces actually have on injuries?

It's a question worth asking because the answers aren't as straightforward as the discourse suggests. Several MLS stadiums currently use FieldTurf, including Mercedes-Benz Stadium (Atlanta), BC Place (Vancouver), Red Bull Arena (New York), Providence Park (Portland), Gillette Stadium (New England), and Lumen Field (Seattle). Players have long complained about synthetic surfaces, but the injury data reveals something more specific than general discomfort. It shows a recovery penalty that varies dramatically by injury type and climate.

To find out what MLS teams should actually expect in 2026, I built a dataset of 8,497 injuries spanning 2008 to 2025. What I found challenges some assumptions about turf while confirming others — and points to a more significant factor that every front office should be planning around.

The Injury Landscape Has Changed Dramatically

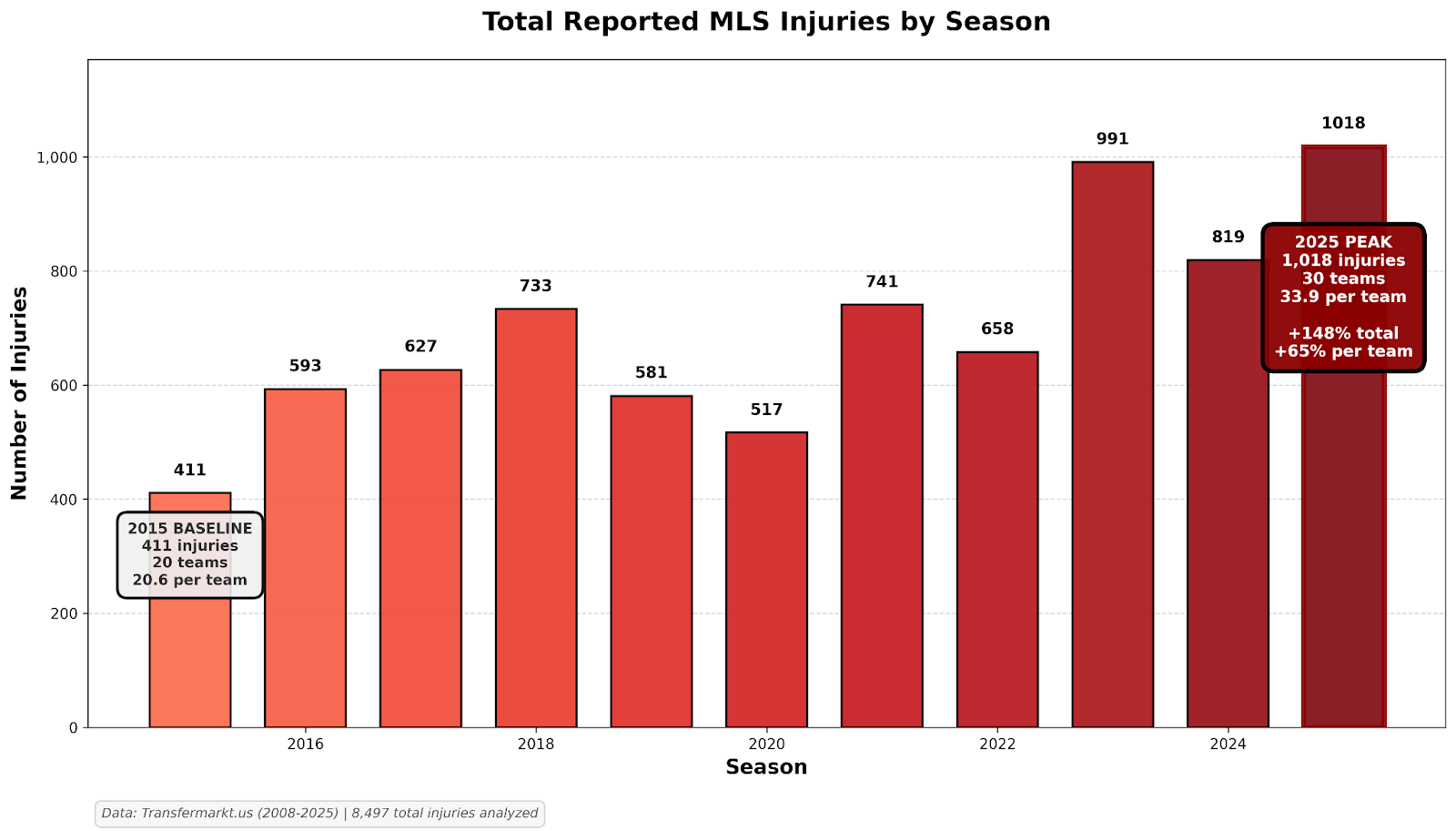

Before diving into surface effects, it's worth understanding how much the baseline has shifted. MLS injuries have increased substantially over the past decade. The league recorded 411 player injuries in 2015; by 2025, that number reached 1,018. Even accounting for expansion from 20 to 30 teams, injuries per team rose from 20.6 to 33.9 — a 65% increase. Based on current trends, teams should expect approximately 30-35 injuries per season in 2026.

This isn't just a story about more teams or more games. Something structural has changed in how the league operates, and the introduction of the Leagues Cup in 2023 appears to be a significant factor. From 2015 to 2022, MLS averaged 608 injuries per season. In 2023-2025, that average jumped to 943, a 55% increase. The compressed schedule and additional competitive fixtures have fundamentally altered the injury calculus for every club.

With that context established, two questions stand out from the data that will shape the 2026 season: how do playing surfaces and climate conditions interact to affect injury recovery, and when during the season are teams most vulnerable?

Before diving deeper, it's important to note some limitations. I'm using data from Transfermarkt for injury collection. I'm also assuming that reporting windows are, more or less, accurate within a day. As anyone who has ever played fantasy MLS before will tell you, this is a big assumption.

The Turf Question Is More Complicated Than You Think

So what does the data actually say about FieldTurf? The overall difference between surfaces appears modest at first: FieldTurf injuries average 64.0 days recovery versus 60.2 days on grass, just 3.8 days longer. But that aggregate masks critical variation. For muscle injuries specifically, FieldTurf recovery times average 74.6 days compared to 43.8 days on grass — a 70% increase. While this difference isn't statistically significant due to high variability (p=0.26), the pattern is consistent across multiple injury types affecting soft tissue.

Here's where the data gets interesting. The injury data from FieldTurf stadiums shows 16.5% of injuries are severe (90+ days), compared to 16.1% on grass — nearly identical rates. FieldTurf doesn't appear to cause more catastrophic injuries (ACL tears, fractures), but it complicates recovery for the common muscle strains that account for most player absences.

So if turf doesn't cause more injuries or more catastrophic ones, why is it so universally detested by players?

The Answer Lies in Biomechanics and Climate

The biomechanical explanation appears the most sound. Modern FieldTurf has lower energy absorption than natural grass, meaning more impact force is transmitted back to the player's body during running, cutting, and landing. This increased ground reaction force creates greater stress on muscles, tendons, and joints — which explains the extended recovery times even when the initial injury rates are similar.